READ

First things first. Where on earth is Comoros? I’d never

heard of it until I started making plans for this project. Turns out it’s an island

nation off the eastern coast of Africa, situated between Madagascar and Mozambique.

It used to be a French colony, which means that I needed to find an English

translation of a book written in French. Unfortunately, it does not appear that

any Comorian novels have ever been translated into English for commercial

publication. Hmmm, what to do?

I did what other people who have embarked on a similar global

reading project have done – I emailed an entreaty to Dr. Anis Memon, a professor at the University of Vermont who has done

his own informal translation of Mohamed Toihiri’s novel, The Kaffir of Karthala. Dr. Memon graciously emailed me a copy of

his translation, and my problem was solved.

The Kaffir of Karthala

opens with the protagonist, Dr. Idi Wa Mazamba, being told by his physician

that he has cancer and has only a year to live. He doesn’t tell his wife, with whom

he leads a fairly loveless existence. He recently met a young woman from France

and a relationship appears to be developing between them, although it is

complicated not only because he is married, but by the fact that he is a black Muslim

Comorian and she is a white Jewish European.

The book is full of descriptions of Comorian life, including

wedding customs, religious rituals, and personal relationships. As the book

proceeds, we also learn more about the government of Comoros when the

President offers Idi a position in his administration. I especially liked this

quote from Idi when he was talking to the President: “To succeed in changing

attitudes you have to begin, Mr. President, by demanding of each of your

ministers that in full council they give you a summary of the books they’ve

read this month, for the mind is like a plant: if you don’t water it, it dies.”

The author of The Kaffir of Karthala, Mohamed Toihiri, served as a Comorian diplomat. According

to Wikipedia, he was Permanent Representative to the United Nations for Comoros,

accredited as Ambassador to the United States, Canada, and Cuba, and he was also

the first published author of Comoros. I enjoyed having the opportunity to

learn about this country from a man who knows it so well.

COOK

The book mentioned a plethora of fruits and vegetables that

grow in the Comorian islands: mangoes, guavas, coconuts, bananas, litchis,

oranges, lemons, almonds, tamarind, grapefruit, wild raspberries, corn, manioc,

and breadfruit, for example. There were also some dishes that sounded like they

might possibly be vegan, if only I had been able to find recipes for the Comorian

versions of them, such as sambosas, nutmeg biryani, and halwa. I decided to

just search online for Comorian recipes, and I found one for soupe faux pois,

or sweet pea soup. The recipe was vegan as written, so I didn’t have to make

any substitutions. The soup was very tasty and a little spicy. It was not

pretty, however, as you can see in the photo below. It was supposed to be

garnished with lime slices and coconut milk, but they were too heavy to stay on

top of the soup. So those Jackson Pollack-type speckles of coconut milk are the

best I could do for the garnish. The recipe was

from a website called InternationalCuisine.com.

GIVE

Finding an organization to receive my donation for this

country was a bit of a challenge. My go-to donation website, GlobalGiving.com, didn’t have any

projects listed for Comoros, so I had to do a little Internet searching. I

found the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, which works to save species from

extinction throughout the world. According to their website, Comoros and nearby

Madagascar “form part of one of the five most important areas in the world for

biodiversity.” However, many species on these islands are being threatened.

Consequently, “Durrell focuses on the most threatened species and the most

threatened habitats of Madagascar and the Comoros. Rural communities depend on

the same ecosystems for their livelihoods, so our approach is based on

empowering these communities to lead in the protection of their local

environments.” I asked that my donation be used for a project in Comoros. More

information about the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust can be found at https://www.durrell.org/wildlife/.

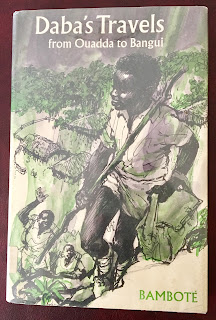

NEXT STOP: DEMOCRATIC

REPUBLIC OF CONGO